Stability in complex food webs

Understanding the link between biodiversity and ecosystem functioning is essential to provide evidence-based policy to conserve and manage ecosystems. Previous research showed that species richness increases community biomass by increasing niche complementarity, and increases community stability mostly by increasing asynchrony in species fluctuations (Thibaut & Connolly, 2013; Tilman et al., 2006). Temporal community stability is often measured as the inverse of the coefficient of variation of biomass/abundance, which can be partitioned into species stability and asynchrony (Thibaut & Connolly, 2013; Zhao et al., 2022). Most of our knowledge on ecosystem functioning is based on a restricted set of organisms, namely plant assemblages, which poorly reflect the complexity of natural communities as they do not include primary and secondary consumers. I have focused on extending our knowledge of the link between biodiversity and ecosystem functioning to more complex communities, i.e. food webs, using empirical and theoretical approaches during two of my post-docs, one at MNHN (Paris, 2018-2021) with Colin Fontaine, Maud Mouchet, and Élisa Thébault, and one ongoing at Sheffield (UK, 2022-now) with Andrew Beckerman.

Effect of species richness and food web structure on temporal stability

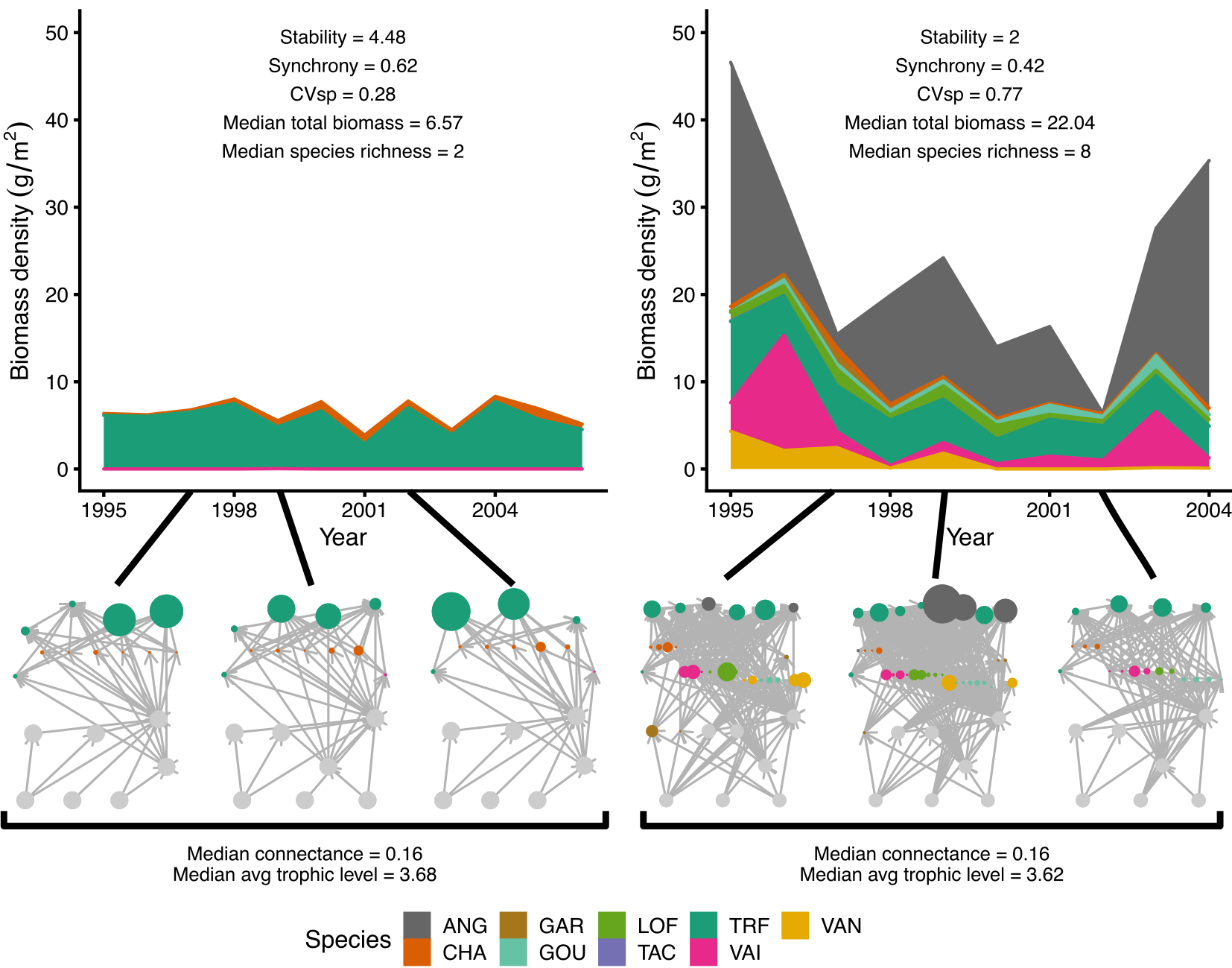

Using inferred riverine food webs as described in the previous part, we showed that both species richness and food web structure determine average total biomass and its temporal stability (Danet et al., 2021). Both fish species richness and average trophic level increased total biomass. We further found that higher average trophic level increased community stability by increasing population stability (i.e. amplitude of species oscillations, Figure 5). And as found previously in simpler species assemblages, species richness was increasing asynchrony in species fluctuations, thereby increasing community stability. In contrast, we found that fish populations were more synchronous than found in previous studies considering simpler species assemblages. We further found that species pairs linked by trophic interactions were more synchrone than species pairs not involved in trophic interactions. We hypothesised multi-trophic communities are characterised by lower asynchrony than simpler species assemblages, because the presence of generalist predators can synchronise the dynamics of their prey. It was difficult to go further in the interpretation because of the lack of other studies to compare my results with. Identifying this key role of generalist predators has strong implications in the current context of generalist, non-native species colonising many ecosystems. Community changes toward more generalist species could trigger a decrease in the diversity of species response to environmental perturbations, i.e. a decrease in response diversity. But it is the diversity of species responses to environmental perturbations that generates asynchrony in species fluctuations and then drives the positive relationship between community stability and species richness. Hence, I was really interested in investigating the effects of the diversity of species response to environmental fluctuations and species richness on temporal stability of complex food webs. I further delved into these questions during my postdoc at the University of Sheffield. My goal was to bring stability-species richness theory and food web theory together, as species interactions (e.g. consumer-resource oscillations) can generate asynchrony on top of response diversity.

Theoretical models

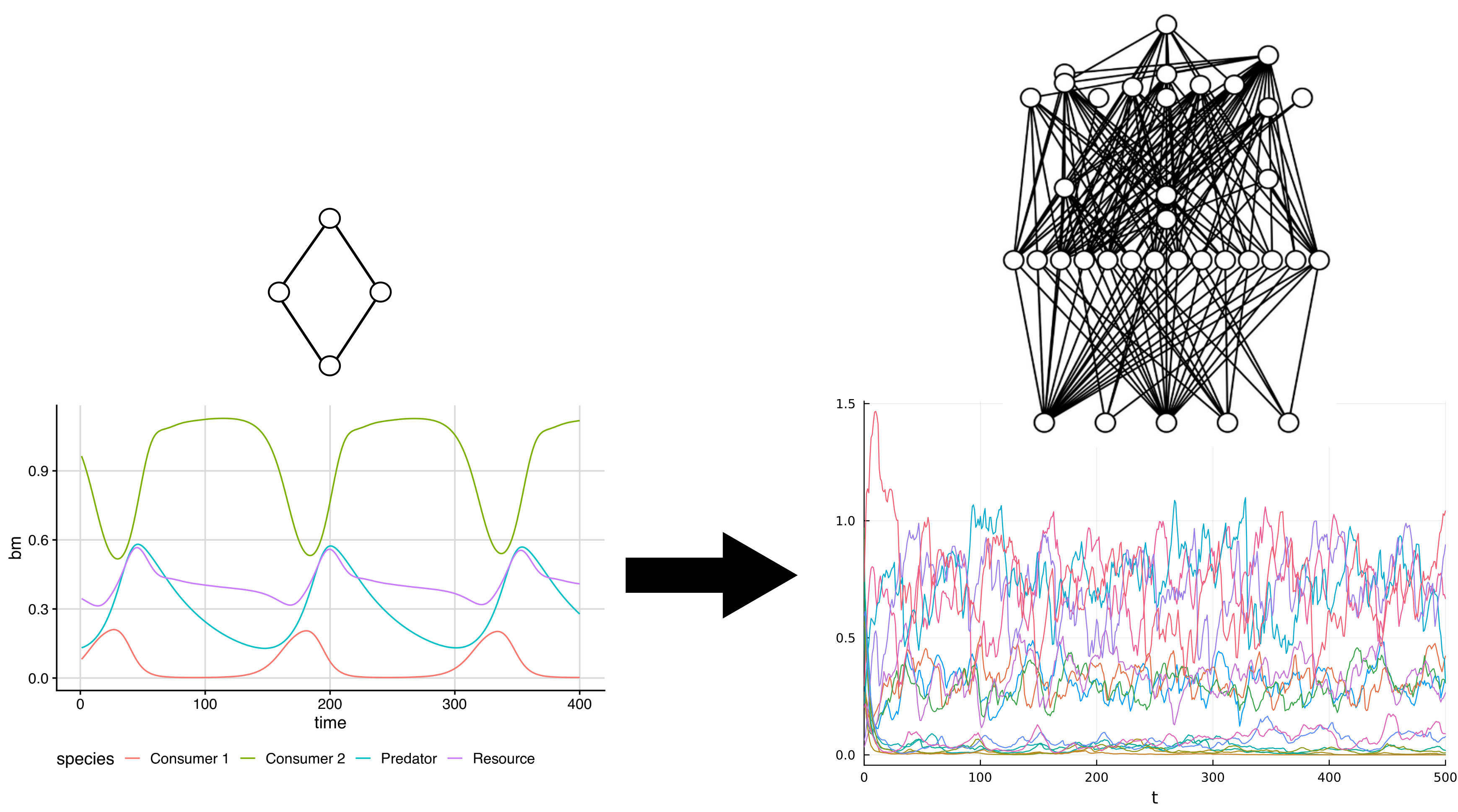

To answer that question, I developed a theoretical model describing the dynamic of species in complex food webs facing environmental stochasticity in their mortality rates. This has been possible through the contribution to the development of a Julia package that facilitates the simulation of such complex communities (EcologicalNetworksDynamics.jl), which I did under the lead with researchers at ISEM (Montpellier) and in particular Ismaël Lajaaiti, Iago Bonnici and Sonia Kéfi (Lajaaiti et al., 2024). My model includes response diversity of species to environmental stochasticity, i.e. the ability of species to respond differently to the same environmental change, the crucial mechanism that generates asynchrony in species fluctuations and then positive stability-species richness relationships. We found that response diversity and species richness jointly increase asynchrony also in complex food webs. food web structural properties, such as average trophic level, connectance (a measure of complexity), and average interaction strength, all decrease asynchrony. We further found, as in empirical data (Danet et al., 2021), that increasing average trophic level increases population stability. Overall, we also found positive community stability - species richness relationships, but only when response diversity was high. High response diversity was indeed increasing asynchrony. However, high number of species interactions (i.e. higher connectance) and high average trophic level were resulting in negative stability-richness relationships, because they were dampening asynchrony (Figure 6, bottom panel). This study thus confirmed our initial hypothesis drawn from empirical fish communities (Danet et al., 2021), namely that trophic interaction can limit asynchrony among species. Then, our research showed that response diversity and species richness increase community stability in complex food webs as in plant communities, but that it depends on food web structure. In turn, we also showed that a decrease in species response diversity and changes in food web structure could lead to a decrease in the stability of ecological communities (Danet et al., in prep).